How to explore Chapter 8

In this chapter, we explore the forgotten stories of women, from China, Japan and beyond, who carried the way of tea, throughout history. We explore the essential connection between the women ancestors of tea, daoism, zen, poetry and the way of nature.

I recommend to start exploring this chapter by listening to the audio file “Chapter 8 - The Matrilineal Story of Chadao”, and the supporting written material. You will also find the video of a tea ritual at the very end of the chapter.

More content will be added to this chapter in the future, as soon as I will be able to make my way back to China and Japan.

I wish you a beautiful exploration.

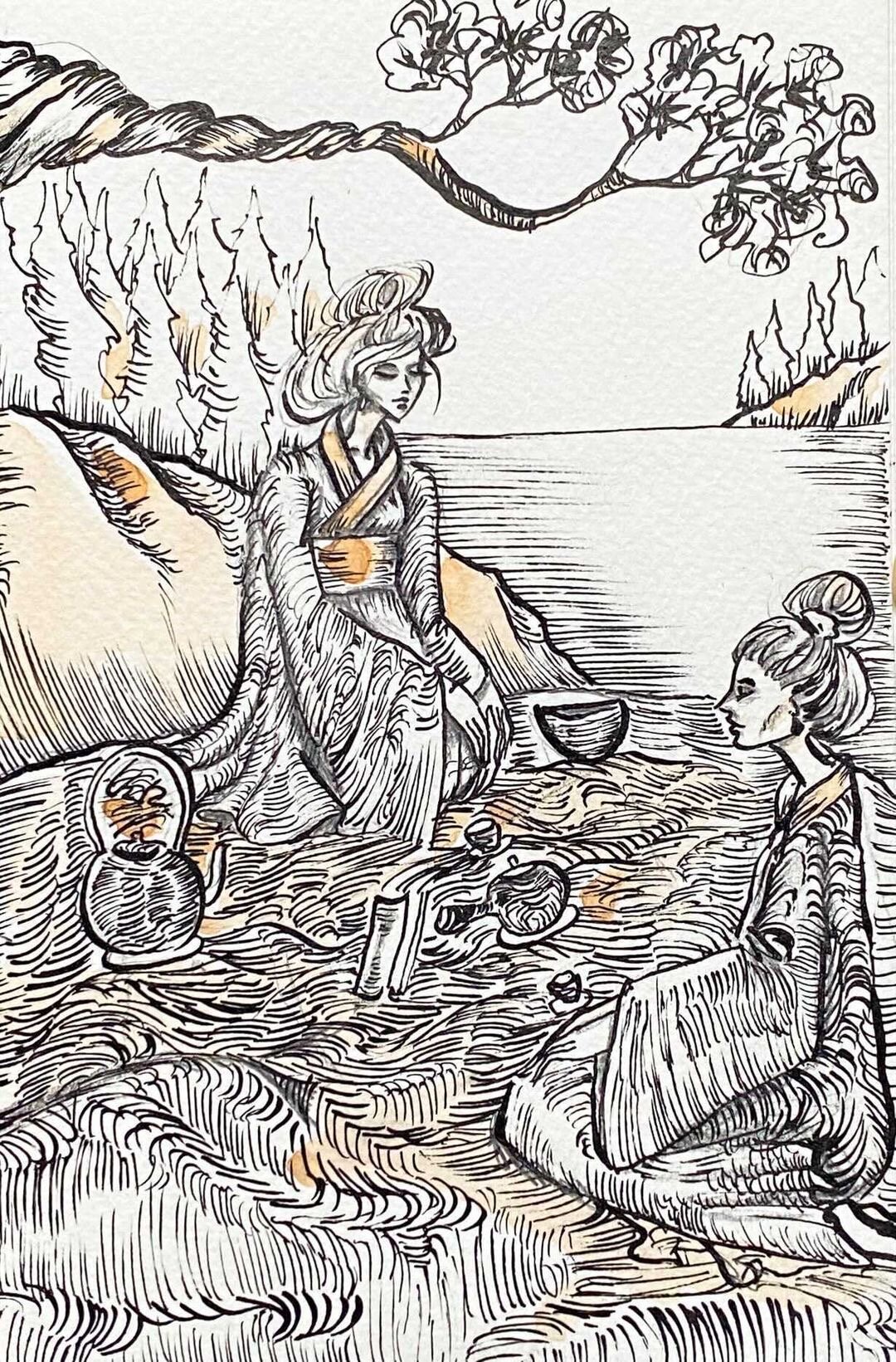

Beautiful tea art, made with pu’er tea, by Snow Seychelle

The Matrilineal Story of Chadao

There is an essential connection existing between our love for tea and our love for nature. Through the story of tea, we learn the story of harmony, alchemy, balance.

Like many of my tea sisters and women teachers, I was initiated to the practice of Chadao, the way of tea, mostly by men. When we explore the history of tea, we notice that it is difficult to find mention of any women’s names and their influence on Chadao. When the plant Camellia Sinensis was first discovered, along the Shang dynasty, the leaves were used as a medicine. Cha (tea) was not yet recognized as a “spiritual practice”. The very first documents found on tea as a path, a way, are dating from a time when the position of women in China (and beyond) was shaped by Confucian gender ideas and norms. The impact of Imperial China on women has been felt all across Asia, and probably the world. The power, which used to belong to the Matriarch, was displaced. The voices and stories of women became invisible, considered “of none important matter”. This can be felt so strongly in the story of tea, chadao, and beyond.

To remember the way of balance, harmony, alchemy, creation - we have to remember the idea that Yin is supporting Yang, the Earth supporting Growth, the Inhale supporting the Exhale. We also have to remember that the Mother and the Father gave birth to the ten thousand mysteries, together.

With the help of tea sisters and brothers from China, Japan and beyond, I have created this chapter to share with you the forgotten matrilineal story of tea. In this chapter, you will find the stories of the women ancestors of chadao, from the past and present.

The women ancestors of tea in China

During ancient and imperial China, women were restricted from participating in various realms of social life, due to strict division of genders. The ritual of tea was considered an activity reserved to “men”.

To trace the presence of women in the story of chadao, we have to trace the story of women in Daoism, Chan, Poetry and the Jiaofang, a high-end school for girls in China, where they were trained in music, dancing, literature, calligraphy, chess and the serving of tea.

To trace the stories of women connected to tea, we can also explore the story of how harmony within Nature was lost. And just like Meena Kumari once said : “Women and the earth have a lot to tolerate.”

Ancient China

During Ancient China, most of the records of women that can be found are those part of the nobility, generally considered passive, under the control of their male guardians or the male of their family. However, women of Ancient China were generally more free and venerated than in later time…

During the Neolithic period, prior to pastoralism and the first social division of labor, most societies were following the matrilineal way. For exemple, the Yangshao culture (5000-3000 BC), who existed along the Yellow River, is said to have been matrilineal. There was female figurines representing goddesses and fertility symbols found at sites of the Hongshan culture (4700-2900 BC). Vessels were also found, from the Majiayao culture (3000-2000 BC), with powerful symbols of female and male genitalia, representing the idea that the Yin force is supporting the Yang force.

By the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256 BC), strict feudal hierarchy changed the idea of balance, and society shifted to become patriarchal. The power of the original Mother was now under the control of the Patriarch. It was now said that “men plow, women weave”. In other terms, most social activities became limited to men. Many practices that we wish to explore today, were strictly considered “male practices”. Which makes it difficult to find any mention of women connected to the practice of Chadao during this period.

During the Spring and Autumn period, most texts were emphasizing women’s inferiority to male. However, female relatives of rulers or upper-class women played important roles in political and social events.

Winter tea, by Snow Seychelle

imperial china

During Imperial China, the rise of Confucian ideology and strict gender roles was guided under the Patriarchal system. During the Qin and Han Dynasty, it was thought that a virtuous woman was a woman following the males in her family. The later Tang Dynasty became a little more open, considered as a “golden period” for women, in contrast to Neo-Confucianism of the later Song dynasty.

It was common during the Tang dynasty to send princesses from the Imperial House to marry foreign rulers to forge political alliances. Far from being passive “objects” of trades, the princesses were expected to act as Tang ambassadors and diplomats to the foreign courts they married.

Princess Wencheng, by unknown artist

In the early Tang dynasty, the princess Wencheng, niece of Emperor Taizong, married the Tibetan king Songzan Gambo, to bring peace between Tang and Tibet. She traveled from present day Xi’an (the capital of the Tang) to present day Lhasa (the capital of Tibet), with tea leaves with her. To help her acclimate to her new home, she began to boil tea leaves, with yak butter and spices every morning. The historical legend of Princess Wencheng influenced the lives of Tibetans, which eventually considered tea leaves an important element of trade with China, a symbol of connection, an important part of their culture. A faster route was necessary for the leaves to be traded from China to Tibet, which gave birth to the famous ancient tea horse road, the Chamadao 茶馬道

Women of the Tang Dynasty are often appearing in tales as powerful spirits occupying powerful positions in social consciousness (shamans, daoist priestess, poetess, concubines of important leaders, courtesans). To be a courtesan required to be incredibly educated and literate. The most admired poetess, priestess and chadao women ancestors were often courtesans. They were incredibly intelligent and well educated, as they had to learn poetry, dance, singing and the art of tea, to entertain their clientele of important leaders.

Jiaofang 教坊

The flourishing story of courtesans in the Tang Dynasty was probably due to the foundation of a new governmental administration called Jiaofang (教坊), an instruction quarters and high-end school for girls. They trained in music, dancing, literature, calligraphy, chess and the serving of tea. The Jiaofang system lasted several centuries, until the middle of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911). Courtesans trained in Jiaofang were considered “official courtesans”, providing entertainment for leaders and scholars.

Li Ye

Also known by her courtesy name Li Jilan, was a Tang dynasty Chinese poet, courtesan, Taoist nun and entertainer, known for her talent in poetry, for her connection to chadao and for her beauty. She was the lover of the renowned Lu Yu, the first to ever write a book on tea, The Classic of Tea, an important legacy in the history of Chadao. It is possible that he received the help of Li Ye secretly in the creation of this book, but this piece of the story will be forever hidden.

Li Ye was admired for her literary talent and she was summoned to the court of Emperor Daizong of Tang to compose poetry for him, from 766 to 779. As a courtesan, Li Ye was known for her beauty and grace, her talent for poetry, music and calligraphy. She was the friend of the renowned poet and Buddhist monk Jiaoran.

As an entertainer, the ritual of tea was part of the offerings of Li Ye. In the tumultuous years of the late Tang dynasty, in 784, she was forced by the rebel leader Zhu Ci to write political poems denigrating the Imperial House, was accused of treason and condemned to death. She is one of the very rare Tang-dynasty women whose poetry survived.

“ What is closest and farthest apart? East and West?

What is deepest and most shallow? the clear brook?

What is highest and brightest? the sun and the moon?

What is the most intimate and most estranged?

A man and wife. “

- Li Ye

To be intelligent, witty, courageous and beautiful during Imperial China would most often lead women to be punished, their reputation would be destroyed maliciously or they would be condemned to death.

“An Amorous Woman of Tang Dynasty” featuring the life of Yu Xuanji

Yu Xuanji

Famous female poet of late Tang, who loved practicing chadao. A tea was named after her at the time, the Yuxuanji cha. She wrote poems inspired by her connection to Chadao, the way of tea. In her twenties, she was accused of beating her maid to death — accusations that was likely false, probably created by a rival, or may simply be a reflection of the traditional distrust of women who were strong-willed and sexually independent at the time. Her poems are still alive, displaying her liberal, individualistic nature. Today, she is considered by many as an early feminist icon and recognized to be China’s first openly bisexual female. Her story inspired many movies and books. In 1915, she was the subject in the short story “Gyogenki” by the Japanese author Mori Ogai. In 1984, a production studio in Hong Kong made a film about her life entitled “An Amorous Woman of Tang Dynasty” (唐朝豪放女). In 1988, a television network in Hong Kong filmed an anthology drama series about her life, titled “Those Famous Women in Chinese History” (歷代奇女子).

“ I entrust my bitterness to a lute’s crimson strings,

Hold back passion - my thoughts unbearable.

Long ago I knew that a cloud-rain meeting

Would not give rise to an orchid heart.

Estranged, but not for long - in the end I shall follow my will,

In flourishing and fading I emptily perceive the nature

of my original mind. ”

- Yu Xuanji (844-68)

During the Song Dynasty, the rise of Neo-Confucianism had a terrible impact on the status of women. From that period, restrictions on women became the most pronounced, where practices like foot-binding and widow chastity became normalized.

Li Qingzhao, by an unknown artist

Li Qingzhao

Poetess of the Song dynasty, who wrote many cha (tea) related poems. She appreciated drinking Tuan tea. She was married to Zhao Mingcheng, a famous poet and politician of the Song dynasty.

Both Li Qingzhao and Zhao Mingcheng loved to read and to collect books. When Zhao Mingcheng would prepare tea, he would invite Li Qingzhao to share the practice with him. Together, they created a sort of “tea and literature game”. One person would have to share an excerpt of a book, and the other would have to guess from which book this excerpt was from. If the answer was found, the “winner” could drink the tea. Li Qingzhao had an incredible memory, and would win all the time. She would drink so much tea. It was rare for a woman at the time to have access to this plant medicine. Due to her strong memory and knowledge of books, she had the chance to drink tea often. It can be felt through her poetry.

“ The pale sunlight of late autumn gradually shines on the patterned windows, and the sycamore trees should resent the cold frost visiting at night. I love to savor the strong, bitter flavor of tea, and wake up in the middle of a dream to enjoy the refreshing aroma of incense. ”

- Li Qingzhao

During Ming and Qing dynasty, Widow chastity was seen as admirable. Women were often committing suicide to protect their honor, often referred as cultural heroes, or martyrs. Confucian principles were strict, guided by the patriarchal system, limiting women to activities that could be conducted within their home, such as weaving. If a woman wasn’t from a high status or the wife of an important leader, to “ liberate ” herself, her only options were to become a courtesan or a Taoist nun, sometimes both at the same time.

Liu Shi

Courtesan and poetess who lived during the transition of the Ming and Qing dynasties, and connected to Chadao. She was one of the most independent figures in the history of Chinese women. Her story is admired for going against the traditional gender roles of the time. She was interested in the famous scholar Qian Qianyi and bought a boat to pursue him. She was often wearing what was considered “men’s clothes”, carrying an air of authentic elegance, and was living the life of a hermit. The scholar Qian Qianyi fell in love with her writings, and became her husband. Liu Rushi was refusing to surrender to the reign of the Qing government, often involved in anti-Qing movements.

“ The mist brushes the green grassland in the night cool ; Fallen cherries darken the emerald pond. Already I resent how the willow catkins resemble tears ; But now the spring wind and spring dream wiff me along. “ - Liu Shi (1618-64)

MEao sang, a timeless matrilineal symbol

The story of Meao Sang inspired the feminized buddhist representation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, originally a “masculin” deity, who gradually took the form of a “feminine” deity in China, through a long transition of thousand years.

Meao Sang was the daughter of a royal family, who refused to marry an important general of her time, choosing instead to dedicate herself to spiritual development, with the intention to serve her community, as a healer. She would travel to different places, wearing a long white robe covering her feminine figure, to help people in need, to offer advices and to offer healing presence. Meao Sang was admired for renouncing her own personal enjoyment as a princess, to serve others. Her story inspired the recognition of the Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, the feminization of the Bodhisattva, an important symbol for all the women in history who saw achievement as a dedication to serving and nourishing others.

Guanyin, or Guan Shi Yin, is for “observing the Sounds (or cries) of the world”. Guanyin is the most popular “woman” deity in China today. And just like the plant Camellia Sinensis, she is an embodiment of love and compassion. Her story is similar to the story of Camellia Sinensis. Both the Guanyin and Camellia Sinensis were under patriarchal dominance for millennia, and both are symbolically representing the power of the original Mother, the balance between the forces of Yin and Yang. The Guanyin and the plant Camellia Sinensis both are representing the balance between grace and strength, compassion and resilience.

*On the photo above, the Guanyin in our tea space, holding a Camellia Sinensis seed and a vessel of Water made of the world’s tears of love and pain.

Xi Wangmu

Xi Wangmu (Hsi Wang Mu) is one of the most ancient and powerful female deity of China. She lives between heaven and earth, in a garden hidden in the clouds. She carries the eternal way of the infinite unceasing cycle of birth and death. She governs the realm of death, as well as the blissful vital force of life.

Her name Xī Wáng Mǔ (西王母) comes from Mǔ for Mother and Wáng for Sovereigh, the Queen or the Honorable. But the term Wáng Mǔ is usually referring to “Grandmother”, the Mother of all Mothers.

She lives on the Jade mountain, and serves as a guardian to women of the dao, since the dawn of time. All of her life, she is tending to the garden of immortality, thriving with fruits, rare flowers, herbs and plants.

The legend of her story shares that she was once a wild demon who eventually found enlightenment, and became a goddess and guide for women of the way. Just like the plant Camellia Sinensis, she carries the many forces of creation, and shares the medicine of truth. Just like the way of tea, she is representing the importance of honoring every phases of the cycle.

Japanese tea hut, by Snow Seychelle

The women ancestors of tea in Japan

For many centuries, chadō in Japan was only reserved to men. Since the dawn of time, the practice of chadō in Japan has been part of a long journey of empowerment and liberation for women. The name of the women ancestors directly connected to chadō (the way of tea) in Japan remains unclear, prior to at least the Edo period. To trace the stories of the women ancestors of tea and chadō in Japanese history, we have to trace the stories of women who followed the way of Zen buddhism, the stories of zen nun, or the stories of women disciples or relatives of important men and monks who carried the way of tea in Japanese history. Tea and Zen are weaved together, in essence.

Heian period

It is unclear in the history who were the women connected of the way of tea during the time of its arrival in Japan, the Heian + Kamakura periods. To trace the name of women who might have been connected to tea during these periods, we have to trace the stories of the women who were connected to Zen lineage, the monk Kukai or the monk Eisai, two monks responsible for carrying tea from China to Japan.

Tachibana Kachiko (786-850)

An Empress, nun, carrier of Zen lineage, and probably connected to chadō, due to her path. She founded the very first Zen temple in Japan, in the west of Kyoto, the Danrin-ji temple. She had heard of Chan (Zen) from the monk Kukai who had visited China. Kukai is known for being the very first to bring tea to Japan. He also founded the Shingon school, an esoteric mantra school of buddhism. Tachibana Kachiko sent a Japanese monk to China, in the hope that it would send her back a teacher that could share the transmission of Chan (Zen) . She was then connected to the disciple Yikung, who became the first abbot of the Danrin-ji, the temple that she founded. The temple was eventually destroyed by fire in 928. But we can still celebrate that the very first zen temple of Japan was founded by a woman, the empress and zen nun Tachibana Kachiko, who most probably came across tea along her journey, due to her connection to the monk Kukai and the way of zen, both important pieces of the way of tea in Japan.

Kamakura period

Shogaku

A nun and distant relative of Dōgen Zenji, the founder of the Zen Sōtō school in Japan, and a disciple of Eisai, who was a monk known for being the first to bring Camellia Sinensis seeds to Japan, so the plant could grow in Japanese soil. Shogaku was most probably connected to the practice of chado, due to her close connection to important carriers of the practice and plant.

Mugai Nyodai (1223-1298)

One of the most important women in Rinzai Zen. She established the temple Keiaiji, the first sodo for women in Japan. Her enlightenment story is famous. She was carrying a bucket of water, maybe to make tea, when the bottom broke out; at that moment she awakened. Due to the strong connection between Rinzai Zen and Chado, it is said that she was probably connected to the practice.

Muromachi period

Eshun (14th century)

Sister of the prominent Soto teacher Ryoan Emyo, abbot of Sojiji and other temples. She was refused to be ordained due to her beauty. Like many women of her time dreaming of being ordained, she shaved her head and scarred her face. After being ordained, she was surpassing all the monks in Zen debate. One of her famous saying was “For one living the Way, hot and cold are unknown”. She was a woman of the Way and probably connected to the way of tea along her journey.

Edo period

Some of the women who were connected to chadō during the Edo period may have studied formally with a teacher, enrolled in a school, attended tea gatherings within their family or simply learned about tea culture through books. If we refer to popular art of the time, we can see that women tea practitioners were represented, either in art or literary work, and were part of the popular culture. Geishas, for similar motives than the courtesans of Imperial China, would often learn the art of tea as part of their education, to entertain their guests. But women were not the focus of the records from that period, and often, researchers know nothing about them, except the name of their husband or father.

For example, it is widely recognized that the second wife of Sen no Rikyū, Sōōn, was connected and familiar with the practice of chadō.

Students of tea in Japan were expressing disinterest in women’s tea practice in general, giving it a negative connotation, assuming that women were not serious enough or were lacking “spirituality”. Yoshiaki Yamamura once said that “the disappearance of Zen spirit was a necessary consequence of feminization of the tea ceremony”. Many shared the belief that “the presence of women in tea culture caused the degradation of the true spirit and authentic traditions of the practice”. This is why there is no direct connection between the women ancestors and the practice of Chado in Japanese history, all until the following periods.

Soshin (1588-1675)

Born into a prominent samurai family, and lived in a subtemple founded by her father, an important Rinzai Zen temple in Kyoto. She instructed the court ladies in Zen, in the Tokugawa shogun’s household in Edo (Tokyo), supported Confucian scholars, and eventually came to have influence in the government. She studied with the Rinzai master Takuan Soho, was ordained a nun in 1660 and made abbess of the Rinzai temple Saishoji in Edo, where she had many women students. She left important Zen writings as a legacy. Due to the important connection between Rinzai Zen and Chado, she was probably connected to this practice.

Ryōnen Gensō (1646-1711)

Rinzai buddhist nun and artist of the 17th century, daughter of a tea master and artist. Celebrated for her spiritual and artistic achievements, Ryonen was known for her beauty and intelligence. She was born from a noble family, got married to Matsuda Bansui, and had many children. Later in life, she was longing for a monastic life, but was refused to the monastery, due to her beauty, considered a distraction. Out of determination, she burned her face. She was eventually accepted, and devoted herself to the path of zen nun.

“ Formerly to amuse myself at court I would burn orchid incense;

Now to enter the Zen life I burn my own face.

The four seasons pass by naturally like this,

But I don't know who I am amidst the change.

In this living world

the body I give up and burn

would be wretched

if I thought of myself as

anything but firewood “

- Ryōnen Gensō

Myotei (17th century)

A nun who sometimes used her own nudity as an empowering way to share her teaching and who was admired for passing the most difficult koans of Rinzai Zen.

Teijitsu (18th century)

She was head of Hakuju-an, a women’s temple where Soto nuns that were displaced and no longer allowed to stay at Eiheiji could stay. It was a time of very strict prohibitions on women in social and political life in Japan, and women monastics were given even less independence than before. She is one of the last woman of the period that had her name recognized.

Meiji period

The people of the narrative of Japanese tea history prior to the Meiji period were men ; either wealthy merchants or warriors serving military and political leaders. It is during the Meiji period that women started to appear more in the story of tea in Japan.

As an example, the Urasenke school was not opened to women until the late 19th century, following the Meiji Restoration. But still, to obtain an important position and be recognized as a carrier of a Japanese tea line like Urasenke or Omotesenke (two lines from the Sen no Rikyū legacy) was difficult, since it is usually hereditary and passed down in a patrilineal system.

During the Meiji period, the practice of chanoyu was added to the instructional curricula of women’s schools, as a way to train young women in proper etiquette, manners, and aesthetics (in a strange misogynistic way). There were variations in the way temae (tea procedures) were taught to women and to men in schools. The procedures were usually very “feminized” in women’s curricula, focusing more on the form, and less on the spirit of tea.

Today, even if women represent the majority of tea practitioners and teachers in Japan, they are usually not able to hold positions of authority within the tea schools. Women are generally still marginalized in the institutions of tea culture, unable to ascend to head positions, or be recognized as leaders. Their presence in literature on tea culture is usually remaining invisible. Most students of tea culture in Japan do not perceive women’s practice and story as an interesting topic to explore, possibly due to the lack of information on the presence of women in the history.

By shifting our focus to the presence of women in the story of tea in Japan, we are reminded to explore beyond the formality of records. We may notice that tea was a means of gender empowerment for women in Japan. It has always been a way for women to get out of the role of the “housewife”. The knowledge gained through the practice of chado was a way to uplift the social status of women, so they could have an impact.

Rengetsu

Illegitimate child of a geisha and a samurai, who was adopted by a temple priest. She was not able to inherit the temple of her adopted father, simply because she was a woman, but her practice and training was really strong. She was recognized for her practice in calligraphy, pottery and jujitsu. She was refused to monastic life because of her beauty, and scarred her face in order to enter the monastery. Rengetsu was regarded for her talent in creating vessels for the ritual of tea and poetry related to tea.

Mitsu Suzuki (20th century)

She was an important carrier of Chado (the way of tea). She was married to Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, and dedicated to the path of zen and the way of tea. She taught at the San Francisco Zen Center for many years, a center founded by her husband, where she shared the wisdom of the Way of Tea. I recommend exploring her book “ A White Tea Bowl “.

Kaoru Nakai (Nakai Sensei)

Certified instructor of Urasenke tea ceremony, Furyuu Sencha ceremony and Chikusenryu flower arrangement. She is associated with the Senryū-ji Buddhist temple in Kyoto, where she is currently still teaching. She is performing her style of Senchado for the imperial family on special occasions.

The matrilineal story of tea, today

In China and Japan today, many women have discovered tea on their own, and very often the practice has been passed down to them from parents and family members. The practice of tea, Gong fu cha, is part of many traditional rituals to celebrate different occasions, such as the New Year and the changing of the seasons, where it is customary to visit elders and offer tea. Sometimes tea is taught as part of training in martial arts or other Taoist practices. Since it was rare to find female teachers of Chadao in ancient times, most women in China and Japan have studied the art of tea and the practice of Gongfu cha, Senchado or Chanoyu, from male teachers or from members of their community or family.

In this section, I share the stories of friends and sisters of Chinese and Japanese lineages with whom I have the honor to explore the way of tea.

Jade & Marissa, Yunnan, China, 2015

Marissa

It was an absolute delight and honor to connect with Marissa, in the tea forest of Lincang, West of Yunnan province, China. Marissa studied tea with her father. She had the occasion to study english abroad, and eventually returned to China to help her family’s tea farm and business. I had the chance to study Gong fu cha with her, as well as exploring the most ancient tea forests, native to the region of her home, where the tea business of her family is located, in Fengqing, China. She introduced me to the “mother tree”, considered to be over 3500 years old. We sat in meditation together near the tree, walked in the forest, spent time with indigenous Camellia Taliensis trees, shared many traditional meals and many cups of tea, mostly pu’er and red tea.

Her favorite tea is the Dianhong cha (red tea from Yunnan province) that her family is producing.

KEIRA

I have met Keira while living in Vancouver, Canada, many years ago. Her chadao practice instantly resonated, as she also recognize the elemental wisdom of tea in her teaching. She was born in Wuzhou, China. She studied tea in Fujian, China and in Taiwan.

In her own words, “tea brings people together”. She believes that “women understand the spirit of tea better, serving tea with grace and feelings”. She also believe than “men are approaching tea in a more technical way, awakening the full potential of the tea”. Keira studied Chadao with men teachers and researchers. Her practice is a fusion of spiritual and sensitive connection to tea, as well as a very structured and technical approach.

Her favorite tea is any Hangzhou Lu cha (green tea from Zhejiang province).

Duo Duo, harvesting leaves at her family’s tea farm, in Fujian, China

Duo Duo

The knowledge and experience of Duo Duo is incredibly vast. She lives in Bejing and has been working at her family’s tea farm in Fujian for the past 15 years, where she assists in the harvest of tea leaves and the production of tea. Her relationship to the plant Camellia Sinensis, from a young age, allowed her to connect with the practice on her own. Like many women of her generation who grew up with a strong connection to the plant, the plant itself becomes the teacher. Duo Duo not only has a strong connection to the plant, ritual of gongfu cha, and tea vessels, but also to the matrilineal story of chadao. I am grateful for the many stories that she has shared with me, allowing me to better understand the situation of women carriers of Chadao.

Her favorite tea is the bai cha (white tea) that her family is producing, at their farm in Fujian province.

Joy

Joy has been teaching Chadao for the past 8 years in her beautiful tea space, located in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. Her teaching is mainly focused on the art of gongfu cha, as a mindfulness practice.

Many years ago, on a rainy day, she visited an old friend who offered her tea. They shared tea in silence, in the form of a meditation. She had a strong connection to the plant, and decided to study and explore the practice.

In her own words…

“ Tea is one of the living forms with the highest vibration in the material world. The action of tasting tea and being present to tea can make us return to our own heart. Smell the fragrances, feel the flow of tea moving into the body, receive the information of this plant, the journey of nature. When the tea enters the mouth, the taste, the breath it invites you to take, the gestures, the expression of the tools and vessels used to make the tea, the water - all of this makes us feel the changes, the way of tea. It is a container giving us unlimited space for exploration. ”

Her favorite tea is any beautiful old gushu sheng pu’er.

NORIKO

I had the occasion to connect with Noriko while I was working at O5 in Vancouver, many years ago, prior to founding WAOTEA. Noriko is a carrier of the Urasenke line of Japanese tea ceremony. She received the transmission of this practice through her mother, who was blessed to be able to reach an important position in the school, which is very rare for women, even today. Her knowledge and experience is very rich and vast. If you ever visit Vancouver, I highly recommend that you take a moment to connect with Noriko.

Yunnan, home of matriarchal communities

Yunnan, where the plant Camellia Sinensis was first discovered, millenium ago, is home of many autonomous, independent tribes, who preserved their customs, culture, language and social views, since the dawn of time. Gift by the blessing of isolation, tribes of Yunnan province were protected from assimilation to the rest of China. Most of the tribes of Yunnan function just like ancient times, under a matriarchal structure.

Many years ago, while I was living in Yunnan, I had the chance to spend time in Dai, Hani and Yi autonomous regions. It is believed that the Hani people were among the first people in Yunnan to produce pu’er cha in ancient times. Hani people, like their descendent, the Yi people, are carrying the ancestral line of the Qiang people, originally from Tibet. The Yi, their descendent, created the Nanzhao Empire in Yunnan during Tang dynasty (7-10 centuries) and grew their economic system from trades along the Tea Horse Road (Chamadao), and are especially known for trading.

“ Hani ” means “strong, fierce women”. And just like any people of Tibetan descent, they are matriarchal in structure. Hani’s religion is based on honoring the forces of Nature. They consider the existence of different souls, the elements, that they call “Yuela”. One of their traditions is the recital of the names of their Hani ancestors, from the first Hani family down to them, so they can always remember and honor their origin.

Other communities, accros the south west of China, in Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou provinces, like the Mosuo ( 摩梭 ), are also following a matriarchal way of life.

The dance of water and leaves

水 茶葉

This tea ritual is shared in honor of the many women ancestors who carried the dance of Water and Leaves, in silence…

TEA COURSE PACKAGE

If you are supporting your practice with the tea course package, for this chapter, we explore Muladhara Shu Pu’er, leaves from wild indigenous trees of the region of Menghai, Yunnan, China.

Muladhara Shu Pu’er carries the deep nourishing wisdom of the Earth element, an invitation for introspection, meditation, absorption, presence.

The Way of Tea Course

CONTENT

Chapter 1

The story of Tea

Chapter 2

Theory of Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Theory of Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Gong Fu Cha Theory

Chapter 5

Theory of Japanese Tea History

Chapter 6

Creating your Tea Offering